As the casual reader of this blog (or my book) will be aware, I like to delegate my trading to systems, since humans aren't very good at it (well, I'm not). This is quite a popular thing to do; many systematic investment funds are out there competing for your money; from simple passive tracking funds like ETF's to complex quantitative hedge funds. Yet most of these employ people to do their risk management. Yes - the same humans who I think aren't very good at trading.

As I noted in a post from a couple of years ago, this doesn't make a lot of sense. Is risk management really one of those tasks that humans can do better than computers? Doesn't it make more sense to remove the human emotions and biases from anything that can affect the performance of your trading system?

In this post I argue that risk management for trading systems should be done systematically with minimal human intervention. Ideally this should be done inside an automated trading system model.

For risk management inside the model, I'm using the fancy word endogenous. It's also fine to do risk management outside the model which would of course be exogenous. However even this should be done in a systematic, process driven, way using a pre-determined set of rules.

A systematic risk management approach means humans have less opportunity to screw up the system by meddling. Automated risk management also means less work. This also makes sense for individual traders like myself, who can't / don't employ their own risk manager (I guess we are our own risk managers - with all the conflicts of interest that entails).

This is the second in a series of articles on risk management. The first (which is rather old, and wasn't originally intended to be part of a series) is here. The final article (now written, and here) will be about endogenous risk management, explain the simple method I use in my own trading system, and show an implementation of this in pysystemtrade.

What is risk management?

Let's go back to first principles. According to wikipedia:

"Risk management is the identification, assessment, and prioritization of risks (defined in ISO 31000 as the effect of uncertainty on objectives) followed by coordinated and economical application of resources to minimize, monitor, and control the probability and/or impact of unfortunate events[1] or to maximize the realization of opportunities. Risk management’s objective is to assure uncertainty does not deflect the endeavour from the business goals. "

This slightly overstates what risk management can achieve. Uncertainty is almost always part of business, and is a core part of the business of investing and trading. It's often impossible to minimise or control the probability of something happening, if that something is an external market event like a recession.

Still if I pick out the juicy parts of this, I get:

- Identification, assessment and priorization of risks

- Monitoring of risks

- Minimize and control the impact of unfortunate events

- Identify some important risks.

- Work out a way to measure them

- Set levels at which action should be taken, and specify an action to take.

- Monitor the risk measurements

- Take action if (when) the measurements exceed critical levels

- When (if) the situation has returned to normal, reverse the action

I would argue that only steps 1,2 and 3 are difficult to systematise. Steps 4 to 6 should be completely systematic, and if possible automated, occuring within the trading system.

Types of risk

It's very easy to forget that there are many types of risk beyond the usual; "the price will fall when we are long and we will lose our shirts". This is known as market risk and whilst it's the most high profile flavour there are others. Pick up any MBA finance textbook and you'll find a list like this:

- Market risk. You make a

bettrade which goes against you. We quantify this risk using a model. - Credit / counterparty risk. You do a trade with a guy and then they refuse to pay up when you win.

- Liquidity risk. You buy something but can't sell it when you need to.

- Funding risk. You borrow money to buy something, and the borrowing gets withdrawn forcing you to sell your position.

- (Valuation) Model risk.You traded something valued with a model that turned out to be wrong. Might be hard to distinguish from market risk (eg option smile: is the Black-Scholes model wrong, or is it just that the correct price of OTM vol is higher?).

- (Market) Model risk. You trade something assuming a particular risk model which turns out to be incorrect. Might be hard to distinguish from market and pricing model risk ("is this loss a 6 sigma event, or was our measurement of sigma wrong?"). I'll discuss this more later.

- Operational / IT / Legal risk. You do a trade and your back office / tech team / lawyers screw it up.

- Reputational risk. You do a trade and everyone hates you.

Looking at these it's obvious that some of them are things that are hard to systematise, and almost impossible to automate. I would say that operational / IT and Legal risks are very hard to quantify / systematise beyond something like a pseudo objective exercise like a risk register. It's also hard for computers to spontaneously analyse the weaknesses of valuation models, artifical intelligence is not quite there yet. Finally reputation: computers don't care if you hate them or not.

It's possible to quantify liquidity, at least in open and transparent futures markets (it's harder in multiple venue equity markets, and OTC markets like spot fx and interest rate swaps). It's very easy to program up an automated trading system which, for example, won't trade more than 1% of the current open interest in a given futures delivery month. However this is beyond the scope of this post.

In contrast it's not ideal to rely on quantitative measures of credit risk, which tend to lag reality somewhat and may even be completely divorced from reality (for example, consider the AAA rating of the "best" tranche of nearly every mortgage backed security issued in the years up to 2007). A computer will only find out that it's margin funding has been abruptly cut when it finds it can't do any more trading. Humans are better at picking up and interpreting whispers of possible bankruptcy or funding problems.

This leaves us with market risk - what most people think of as financial risk. But also market model risk (a mouthful I know, and I'm open to using a better name). As you'll see I think that endogenous risk management can deal pretty well with both of these types of risk. The rest are better left to humans. So later in the post I'll outline when I think it's acceptable for humans to override trading systems.

What does good and bad risk management look like?

There isn't much evidence around of what good risk management looks like. Good risk management is like plumbing - you don't notice it's there until it goes wrong, and you've suddenly got "human excrement"* everywhere*Well my kids might read this blog. Feel free to use a different expression here.

There are plenty of stories about bad risk management. Where do we start... perhaps here is a good place: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_trading_losses.

|

| Nick Leeson. Bad risk management in action, early 90's style. Source: Daily Mail |

Generally traders are given a small number of risk management parameters they have to fit within.

For example my first job in finance was working as a trader for Barclays Capital. My trading mandate included a maximum possible loss (a mere million quid if I remember correctly), as well as limits on the greeks of my position (I was trading options). I also had a limit on everyones favourite "single figure" risk measurement, VAR.

Bad traders will eithier willfuly, or through ignorance, bend these limits as much as possible. For example if I return to the list of trading losses above, it's topped by this man:

|

| Howie. The 9 billion dollar man. Not in a good way. Source: wallstreetonparade.com |

Howie correctly called the sub prime mortgage debt collapse. He bet on a bunch of mortgage related derivative crap falling. But to offset the negative carry of this trade (which caused a lot of pain to other people doing this trade) he bought a bunch of higher rated mortgage related derivatives. For boring technical reasons he had to buy a lot more of the high rate stuff.

On paper - and presumably according to Morgan's internal models - this trade had minimal risk. It was assumed that the worst that would happen would be that house prices stayed up, and that the long and short side would remain high. Hopefully though Howie would get it right - the crap would fall, and the good stuff would keep it's value.

However it turned out that the good stuff wasn't that good eithier; the losses on the long position ended up dwarfing the gains on the short position. The risk model was wrong.

(The risk management team did [eventually] warn about this, but Howie succesfully argued that the default rate they were using to model the scenario would never happen. It did.)

Risk management embodied by trading systems

From the above discussion we can derive my first principle of risk management:

Good traders do their own risk management

(and by trader here I mean anyone responsible for making investment decisions, so it includes fund managers of all flavours, plus people who think of themselves as investors rather than traders).

Good traders will take their given risk limits as a starting point. They will understand that all risk measurements are flawed. They will think about what could go wrong if the risk model being used was incorrect. They will consider risks that aren't included in the model.

Similarly good trading systems already do quite a lot of risk management. This isn't something we need to add, it's already naturally embodied in the system itself.

For example in my book I explain how a trading system should have a predetermined long term target risk, and then how each position should be sized to achieve a particular target risk according to it's perceived profitability (the forecast) and the estimated risk for each block of the instrument you're trading (like a futures contract) using estimates of return volatility. I also talk about how you should use estimates of correlations of forecasts and returns to achieve the correct long run risk.

Trading systems that include trend following rules also automatically manage the risk of a position turning against them. You can do a similar thing by using stop loss rules. I also explain how a trading system should automatically reduce your risk when you lose money (and there's more on that subject here).

All this is stuff that feels quite a lot like risk management. To be precise it's the well known market risk that we're managing here. But it isn't the whole story - we're missing out market model risk. To understand the difference I first need to explain my philosophy of risk in a little detail.

The two different kinds of risk

I classify risk into two types - the risk encompassed by our model of market returns; and the part that isn't. To see this a little more clearly have a look at a picture I like to call the "Rumsfeld quadrant"

The top left is stuff we know. That means there isn't any risk. Perhaps the world of pure arbitrage belongs here, if it exists. The bottom left is stuff we don't know we know. That's philosophy, not risk management.

The interesting stuff happens on the right. In green on the top right we have known-unknowns. It's the area of quantifiable market risk. To quantify risk we need to have a market risk model.

The bottom right red section is the domain of the black swan. It's the area that lies outside of our market risk model. It's where we'll end up if our model of market risk is bad. There are various ways that can happen:

An important point is that it's very hard to tell (a) an extreme movement within a market risk model that is correct from (b) an extreme movement that isn't that extreme, it's just that your model is wrong. In simple terms is the 6 sigma event (should happen once every 500 million days) really a 6 sigma event?

Or is it really a 2 sigma event it's just that your volatility estimate is out by a factor of 3? Or the unobservable "true" vol has changed by a factor of 3? Or does your model not account for fat tails because 6 sigma events actually happen 1% of the time? You generally need a lot of data to make a Bayesian judgement about what is more likely. Even then it's a moving target because the underlying parameters will always be changing.

This also applies to distinguishing different types of market model risk. You probably can't tell the difference between a two state market with high and low volatility (changing parameter values), and a market which has a single state but a fat tailed distribution of returns (incomplete model); and arguably it doesn't matter.

What people love to do, particularly quants with Phd's trapped in risk management jobs, is make their market models more complicated to "solve" this problem. Consider:

The interesting stuff happens on the right. In green on the top right we have known-unknowns. It's the area of quantifiable market risk. To quantify risk we need to have a market risk model.

The bottom right red section is the domain of the black swan. It's the area that lies outside of our market risk model. It's where we'll end up if our model of market risk is bad. There are various ways that can happen:

- We have the wrong model. So for example before Black-Scholes people used to price options in fairly arbitrary ways.

- We have an incomplete model. Eg Black-Scholes assumes a lognormal distribution. Stock returns are anything but lognormal, with tails fatter than a cat that has got a really fat tail.

- The underlying parameters of our market have changed. For example implied volatility may have dramatically increased.

- Our estimate of the parameters may be wrong. For example if we're trying to measure implied vol from illiquid options with large bid-ask spreads. More prosically we can't measure the current actual volatility directly, only estimate it from returns.

An important point is that it's very hard to tell (a) an extreme movement within a market risk model that is correct from (b) an extreme movement that isn't that extreme, it's just that your model is wrong. In simple terms is the 6 sigma event (should happen once every 500 million days) really a 6 sigma event?

Or is it really a 2 sigma event it's just that your volatility estimate is out by a factor of 3? Or the unobservable "true" vol has changed by a factor of 3? Or does your model not account for fat tails because 6 sigma events actually happen 1% of the time? You generally need a lot of data to make a Bayesian judgement about what is more likely. Even then it's a moving target because the underlying parameters will always be changing.

This also applies to distinguishing different types of market model risk. You probably can't tell the difference between a two state market with high and low volatility (changing parameter values), and a market which has a single state but a fat tailed distribution of returns (incomplete model); and arguably it doesn't matter.

What people love to do, particularly quants with Phd's trapped in risk management jobs, is make their market models more complicated to "solve" this problem. Consider:

On the left we can see that less than half of the world has been explained by green, modelled, market risk. This is because we have the simplest possible multiple asset risk model - a set of Gaussian distributions with fixed standard deviation and correlations. There is a large red area where we have the risk that this model is wrong. It's a large area because our model is rubbish. We have a lot of market model risk.

However - importantly - we know the model is rubbish. We know it has weaknesses. We can probably articulate intuitively, and in some detail, what those weaknesses are.

On the right is the quant approach. A much more sophisticated risk model is used. The upside of this is that there will be fewer risks that are not captured by the model. But this is no magic bullet. There are some disadvantages to extra complexity. One problem is that with more parameters they are harder to estimate, and estimates of things like higher order moments or state transition probabilities will be very sensitive to outliers.

More seriously however I think these complex models give you a false sense of security. To anyone who doesn't believe me I have just two words to say: Gaussian Copula. Whilst I can articulate very easily what is wrong with a simple risk model it's much harder to think of what could go wrong with a much weirder set of equations.

(There is an analogy here with valuation model risk. Many traders prefer to use Black-Scholes option pricers and adjust the volatility input to account for smile effects, rather than use a more complex option pricer that captures this effect directly)

So my second principle of risk management is:

Complicated risk model = a bad thing

Risk management within the system (endogeonous)

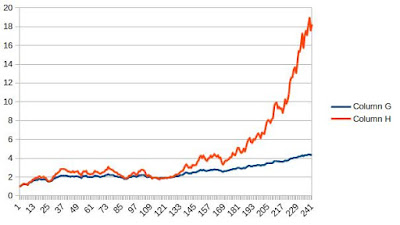

Let's take an example. We know that the model of fixed Gaussian volatility is naive (and I am being polite). Check this out (ignore the headline, which is irrelevant and for which there is no evidence):

|

| S&P 500 vol over time. Source: Seeking Alpha |

Now I could deal with this problem by using a model with multiple states, or something with fatter tails. However that's complicated (=bad).

If I was to pinpoint exactly what worries me here, it's this: Increasing position size when vol is really low, like in 2006 because I know it will probably go up abruptly. There are far worse examples of this: EURCHF before January 2015, Front Eurodollar and other STIR contracts, CDS spreads before 2007...

I can very easily write down a simple method for dealing with this, using the 6 step process from before:

- We don't want to increase positions when vol is very low.

- We decide to measure this by looking at realised vol versus historical vol

- We decide that we'll not increase leverage if vol is in the lowest 5% of values seen in the last couple of years

- We monitor the current estimated vol, and the 5% quantile of the distribution of vol over the last 500 business days.

- If estimated vol drops below the 5% quantile, use that instead of the lower estimated vol. This will cut the size of our positions.

- When the vol recovers, use the higher estimated vol.

It's easy to imagine how we could come up with other simple ways to limit our exposure to events like correlation shocks, or unusually concentrated positions. The final post of this mini series will explain how my own trading system does it's own endogenous risk management, including some new (not yet written) code for pysystemtrade.

Systematic risk management outside the system (exogeonous)

There is a second category of risk management issues. This is mostly stuff that could, in principle, be implemented automatically within a trading system. But it would be more trouble than it's worth, or pose practical difficulties. Instead we develop a systematic process which is followed independently. The important point here is that once the system is in place there should be no room for human discretion here.

An example of something that would fit nicely into an exogenous risk management framework would be something like this, following the 6 step programme I outlined earlier:

- We have a large client that doesn't want to lose more than half their initial trading capital - if they do they will withdraw the rest of their money and decimate our business.

- We decide to measure this using the daily drawdown level

- We decide that we'll cut our trading system risk by 25% if the drawdown is greater than 30%, by half at 35%, by three quarters at 40% and completely at 45% (allowing some room for overshoot).

- We monitor the daily drawdown level

- If it exceeds the level above we cut the risk capital available to the trading system appropriately

- When the capital recovers, regear the system upwards

[I note in passing that:

Firstly this will probably result in your client making lower profits than they would have done otherwise, see here.

Secondly this might seem a bit weird - why doesn't your client just stump up only half of the money? But this is actually how my previous employers managed the risk of structured guaranteed products that were sold to clients with a guarantee (in fact some of the capital was used to buy a zero coupon bond). These are out of fashion now, because much lower interest rates make the price of the zero coupon bonds far too rich to make the structure work.

Finally for the terminally geeky, this is effectively the same as buying a rather disjointed synthetic put option on the performance of your own fund]

Although this example can, and perhaps should, be automated it lies outside the trading system proper. The trading system proper just knows it has a certain amount of trading capital to play with; with adjustments made automatically for gains or losses. It doesn't know or care about the fact we have to degear this specific account in an unusual way.

In the next post I'll explain in more detail how to construct a systematic exogenous risk management process using a concept I call the risk envelope. In this process we measure various characteristics of a system's backtested performance, and use this information to determine degearing points for different unexpected events that lie outside of what we saw in the backtest.

Ideally you'd do this endogenously: build an automated system which captured and calculated the options implied vol surface and tied this in with realised vol information based on daily returns (you could also throw in recent intraday data). But this is a lot of work, and very painful.

(Just to name a few problems; stale and non synchronous quotes, wide spreads on the prices of OTM options give you very wide estimates of implied vol, non continuous strikes, changing underlying mean the ATM strike is always moving....)

Instead a better exogenous system is to build something that monitors implied vol levels, and then cut positions by a proscribed amount when they exceed realised vol by a given proportion (thus accounting for the persistent premium of implied over realised vol). Some human intervention in the process will prevent screwups caused by bad option prices.

Discretionary overrides

|

| Risk manager working on new career. Source: wikipedia |

But is it realistic to do all risk management purely systematically, either inside or outside a system? No. Firstly we still need someone to do this stuff...

- Identify some important risks.

- Work out a way to measure them

- Set levels at which action should be taken, and specify an action to take.

Secondly there are a bunch of situations in which I think it is okay to override the trading system, due to circumstances which the trading system (or predetermined exogenous process) just won't know about.

I've already touched on this in the discussion related to types of risk earlier, where I noted that humans are better at dealing with hard to quantify more subjective risks. Here are some specific scenarios from my own experience. As with systematic risk management the appropriate response should be to proportionally de-risk the position until the problem goes away or is solved.

Garbage out – parameter and coding errors

If an automated system does not behave according to its algorithm there must be a coding bug or incorrect parameter. If it isn't automated then it's probably a fat finger error on a calculator or a formula error on a spreadsheet. This clearly calls for a de-risking unless it is absolutely clear that the positions are of the correct sign and smaller than the system actually desires. The same goes for incorrect data; we need to check against what the position would have been with the right data.

Liquidity and market failure

No trading system can cope if it cannot actually trade. If a country is likely to introduce capital controls, if there is going to be widespread market disruption because of an event or if people just stop trading then it would be foolish to carry on holding positions.

Of course this assumes such events are predictable in advance. I was managing a system trading Euroyen interest rate futures just before the 2011 Japanese earthquake. The market stopped functioning almost overnight.

A more pleasant experience was when the liquidity in certain Credit Default Swap indices drained away after 2008. The change was sufficiently slow to allow positions to be gradually derisked in line with lower volumes.

Denial of service – dealing with interruptions

A harder set of problems to deal with are interruptions to service. For example hardware failure, data feed problems, internet connectivity breaking or problems with the broker. Any of these might mean we cannot trade at all, or are trading with out of date information. Clearly a comparison of likely down time to average holding period would be important.

With medium term trading, and a holding period of a few weeks, a one to day outage should not unduly concern an individual investor, although they should keep a closer eye on the markets in that period. For longer periods it would be safest to shut down all positions, balancing the costs of doing this against possible risks.

What's next

As I said I'll be doing a another post on this subject. The final post will explain how I use endogenous risk management within my own trading system.