You'd be forgiven for thinking I was given my lack of blog posts in the last few months, but I was busy; first promoting "Smart Portfolios" (thanks to all who have bought it), then on the conference circuit (here, here and here), and then more recently I've been preparing the course material for this.

So this is a post about Bitcoin. I have dissed BTC before [and the price has gone from $500 then to ~$13K now FWIW], but in recent weeks there have been many people asking me about it. It seems you aren't allowed to exist nowadays without having an opinion on all things blockchain.

Actually my opinion on Bitcoin and (what I believe are called) 'alt-coins' is the same as my opinion on many things: a deep scepticism blended with almost total agnosticism. Fact is I don't see why I need to have an opinion on this stuff. I have plenty of places to put my investment capital, thank you very much.

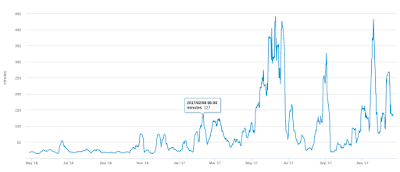

Still 2017 has undoubtedly been the year of the Bitcoin - or perhaps more accurately the last five weeks have been the five weeks of the Bitcoin: people weren't really that interested until the price started going exponential:

Price (bitcoin.com)

Search interest (Google trends)

So it seems appropriate to close 2017 with this post (and the launch of two BTC futures on grown up exchanges in the last few week is also genuine new-news). If nothing else I won't have to continually waste time in replying to the hordes of people constantly asking me what I think about it.

A caveat: I'm writing this as an economist / investor / trader; I'm not a technical expert on the technology side of this stuff. Grab a few pinches of salt - you're going to need them.

A note: The vast majority of this post will apply equally way to any other *Coin. I will interchangeably use the terms bitCoin, BitCoin, bitcoin and BTC.

What is BitCoin for?

Is BitCoin:

- A means of payment (like US dollars)?

- A store of value (like US dollars and Gold)?

- An investment (i.e. a store of value that is hopefully going to go up in price and/or return a stream of payments, like shares in eBay)?

The reason why I ask this is because the people who love Bitcoin started off saying it was going to be a fantastic means of payment, much cheaper and better than boring old existing payment systems (they always use the likes of Western Union as an expensive straw-man for comparison, but international payments are now much cheaper and domestic payments are pretty damn cheap as well).

Now it's late 2017 and it's clear that BTC is currently unsuitable as a means of payment for most transactions:

- It's very expensive (currently north of $50 per transaction)

- The mining process is extremely energy inefficient (each transaction consumes 250kWh; my family of five people and a cat uses about 25kWh a day. If I was to make one bitcoin purchase every 10 days then I'd double our carbon footprint)

- Despite mega hype, hardly anywhere accepts Bitcoins in exchange for real stuff (some that did have stopped)

- The confirmation process is very slow and the time is very volatile (see picture - this is an average: apparently some confirmations take days)

|

| Source: blockchain.info |

It turns out that BitCoin is also currently unsuitable as a store of value:

- The price is extremely volatile. It makes the German mark of the Weimar Republic look like the Swiss franc. Although unlike the inter-war mark it goes up in value as well as down.

- Bitcoins are easily lost or stolen. This is also a problem with cash (though you'd struggle to lose £74 million in fifties), but not so much with 'legacy' electronic payments.

- It turns out to be quite difficult to turn Bitcoins back into real money (see here for just one example) unless you use some foxy derivatives which involves a very high effective transaction fee.

(I'm aware that some people think some of these problems are soluble. I'll come back to that in the 'future of crypto currencies' later)

So all the BTC cheerleaders have now pivoted to saying that BTC is an investment. The logic runs something like this: when all 21 million coins have been mined if the entire world starts using Bitcoin for just 10% of it's transactions then it would need to replace 10% of around $37 trillion in narrow money. $3.7 trillion / 21 million = $176,190 per Bitcoin.

There is an inconsistency here - BTC will only make sense as an investment now if it makes sense in the future as either a means of payment or as a store of value. This is because unlike investment in say stocks or bonds it doesn't produce a stream of earnings or coupons that can be valued. This makes it a bit more like Gold, which people like as a store of value, and if the brown stuff hits the fan it can also be used as a medium of exchange. If we debunk the use of BTC as a means of payment or store of value, then the investment case is also debunked.

People have likened the BTC mania to both the late 90's tech boom and the tulip mania in Holland during the 17th century. Arguably it's worse than both of these. Some of the firms in the late 90's tech boom did have viable businesses and ended up being worth something. If you buy a tulip, at least you have a nice tulip to look at. If you buy a BitCoin you have literally nothing of any intrinsic or aesthetic value.

However the vast interest being shown by people with does make it feel very much like the tech boom, which I remember well (I'm not quite old enough to remember Tulip mania).

What is the future of Bitcoin?

The first thing we need to do is ask how likely it is that the problems outlined above will be soluble anytime soon. This is the most speculative part of the post, because (a) we're looking into the future - which is hard and (b) it's resting on the shaky technical knowledge I have about blockchain technology. I suggest you read this if you want to hear from someone who knows what they are talking about.

Slow: We just need more miners on the case. Of course bandwidth will then become an issue, especially if miners tend to become concentrated in a small number of places with cheap electricity.

Huge power use: Which will only get worse with more miners and a longer block chain. Apparently if you read the bitcoin forums (a) we're going to get really fast computers - quantum computing will allow Moores law to continue, and (b) practically free renewable energy. Even if this is the case I still think it's madness to spend an increasing proportion of our energy budget on book keeping when it can be done much more efficiently by centralised payment systems.

These three points neatly tie together, and there are of course various technical proposals to deal with this. But as far as this dumb economist can tell they all involve fundamental changes in the way that the blockchain works and / or lead to other problems. The blockchain is a fundamentally non scalable thing: it has to get bigger over time, and the more it is used the faster it will grow.

Theft and loss: Essentially you can either:

- opt for a low chance of loss (a third party looks after your coin)

- and risk theft (by the third party)

- or a relatively low chance of theft (you own the physical BTC on a USB or something)

- and risk loss (of the physical object or the password)

Volatility: There is a chicken and egg problem here. The reason for the volatility is that the market cap of coins is relatively low compared to the volume of money moving in and out of them. If the BTC becomes a standard for global payments; and then the market cap of BTC grows sufficiently large, and the volume of money is made up of small transactions rather than large investments, then yes it is plausible that the volatility will dampen down.

Nowhere to spend them: Again chicken and egg. If BitCoin becomes a large enough factor in the world of global payments, then retailers will start accepting them.

Its no surprise that I'm fairly pessimistic about the future of Bitcoin as a true alternative to say US dollars as a medium of exchange or Gold as a store of value.

Of course there is a limited demand for BitCoin and other crypto currencies, made up of people in the following categories:

- People buying stuff they shouldn't buy (eg drugs)

- People who want to hide money from the tax authorities or their spouses

- People who want to convert dirty money into clean money

But there are also existing ways of doing all of these things:

- Most people buy drugs with cash (so I'm told).

- There are plenty of places to hide your money offshore, and most of them have great weather if you want to visit it.

- Money laundering is perhaps the best use of BTC (BTC is great for money laundering. You can put $20 million into your bank account from a crypto exchange and if the authorities want to know where it came from you can tell them you sold two pizzas in exchange for 10,000 BTC in 2010 and they have no way to disprove that).

I would argue that there is essentially an unlimited supply of new currencies (this is different from coin in a given currency), and but quite a limited demand from people who need to use anonymous electronic money. Sure BitCoin has first mover advantage and monopoly power, blah blah blah. But if BitCoin got too expensive then it would sense for the limited pool of people who really need to transact via blockchain to use another cheaper currency, which could be created by someone forking an existing github project which takes about 5 minutes. After all Ethereum is roughly a third the size of BitCoin, despite only being around for 2.5 years compared to nearly 9 years for BTC.

Finally I should point out that the consequences of BitCoin working are really, really, bad. It would mean that governments would lose the ability to tax transactions, and all countries would end up as anarcho-techno states with a ridiculously uneven distribution of wealth. So I'm really hoping this particular experiment doesn't work out.

Should you invest in crypto currencies

I am very skeptical (in case you hadn't realised). But the more interesting part of this post now begins, where I'm going to ignore everything I've just written and assume that there is indeed a valid investment case for BitCoin, and see where that takes us.

What kind of investment is BitCoin?

Bitcoin as an investment has the following characteristics:

- It has limited and unstable liquidity

- It has high bid-ask spreads

- It has high transaction costs (unless you trade the futures)

- The market is fragmented across multiple exchanges

- There are operational and technical difficulties involved with trading it (unless you trade the futures)

- There is counter party risk as you're usually facing an unregulated exchange (unless you trade the futures)

- It is based on a made up number

- It has no asthetic or intrinsic value and does not produce a stream of payments

None of this means you shouldn't invest in Bitcoin. Nearly all of these things also apply to residential housing, and that is still a valid investment. Eurodollar futures are based on a number that we know now, rather famously, has been mostly made up.

But it does mean that if you're investing in BitCoin you should either (a) have a much higher expected return to compensate (b) hold a much small allocation in the asset than you would normally or (c) both.

Should BitCoin have a higher expected return? Indeed should we expect BitCoin to go up in value at all? Luckily we can be agnostic on this subject (since arguing about the long term future of BitCoin is something I'm neither all that interested in or qualified to do).

After all I invest in Gold but not because I personally think it will go up in value. The same goes for tail protect hedge funds. That's because these products bring diversification and provide insurance. It doesn't seem unreasonable to put BitCoin in the same bucket, albeit with the qualifications that Gold (at least when held via an ETF or a future) doesn't suffer from any of the problems I've listed above (Gold does have some industrial uses and enough people seem to like Gold jewellery that it has aesthetic value).

Indeed if we treat BitCoin as an asset with negative correlation to everything else then even a slightly negative expected return wouldn't bother me.

How much should I invest in BitCoin?

Putting aside all my biases this is an opportunity to demonstrate how the top down framework in my book "Smart Portfolios" can be adapted to literally any old crap. Yes, even BitCoin.

The first thing you need to do is decide what your allocation will be to "Genuine Alternatives" (which is my name to distinguish them from not really 'alternative' assets that are very similar to equities or bonds - like the majority of hedge fund strategies).

This in turn is subdivided into the "insurance" and "standalone" buckets; the latter being the rare assets that both provide diversification benefits and also yield a positive return. "Insurance" is the bucket that Gold and Bitcoin sit in, along with certain types of hedge funds and safe haven currencies. Like I said above we don't expect them to provide a positive return, just like I don't expect to make money off buying house insurance in the long run.

In my book I recommend putting between 0% and 25% of your assets into genuine alternatives, and roughly half of that 0-25% into insurance like assets such as Gold, with the other half into standalone alternatives.

Let's first deal with US Investors, since I know from my site traffic report that they make up a majority of readers. My recommended allocation from "Smart Portfolios" for a small US investor is as follows:

- 50% in standalone alternatives of which:

- 25% in managed futures eg WDTI

- 25% in global macro eg MCRO

- 50% in insurance-like of which

- 25% in safe haven currencies eg FXF

- 25% in Gold eg IUA

If we shoehorn BTC into that we get:

- 50% in standalone alternatives of which:

- 25% in managed futures eg WDTI

- 25% in global macro eg MCRO

- 50% in insurance-like of which

- 16.667% in safe haven currencies eg FXF

- 16.667% in Gold eg IUA

- 16.667% in Bitcoin

Sadly for many retail investors in the UK the choice of alternative ETFs is far more limited. From Smart Portfolios :

- 100% in insurance-like of which:

- 50% in Long volatility eg SPVG

- 50% in precious metals

Again if we add BTC:

- 100% in insurance-like of which:

- 33.3% in Long volatility eg SPVG

- 33.3% in precious metals

- 33.3% in Bitcoin

Maximum BTC allocation then is between roughly 4.2 and 8.3%.

However this is a risk weighting. The actual cash weighting is inverse volatility weighted, and so depends on what the risk of the rest of your portfolio would be.

The volatility of BTC is about 100% a year; suggesting that even for someone with a relatively aggressive risk target of around 16% a year (the highest I advocate for reasons explained in the book) they should only be putting a maximum of 0.65% (US) to 1.3% (UK) of your portfolio in crypto.

To reiterate: even with the most aggressive risk target, and the highest recommended allocation to alternative assets, you should be looking to put no more than 1.3% of your portfolio into Crypto.

Notice that I have assumed that BTC will not yield an above average return, but on the other hand I've also ignored all the problems I outlined above (under "investment characteristics" above). The latter argues for a much lower weight (and for me personally that weight is zero). The former argues for a higher weight, but it's worth bearing in mind that it's very difficult to predict the future returns of any asset; and this is doubly true for something like BTC.

How should I invest in BitCoin?

Many of the operational issues with BitCoin relate to owning physical coin. Right now the only alternative is to own the futures; BitCoin ETFs aren't yet available (though perhaps soon will be, but when they become available will be based on the futures).

The futures are very illiquid, although admittedly they have only just been launched. They are cash settled which is good (personally I want to be as far as possible away from 'physical' BTC) and bad (the settlement price is open to manipulation and the price could easily deviate from what the cash and carry arbitrage should produce: but then that's just comparing one imaginary number with another, so fill your boots). They aren't that suited to investors who aren't comfortable with derivatives.

I wouldn't personally buy spot BTC - it's just too flaky. However if you follow my advice and only put ~1.5% of your portfolio into them I suppose that limits your likely risk (if you'd put 1% of your wealth in BTC a year ago you'd be up 10% of your wealth now, which for most portfolios would be a very handy chunk of money).

I might trade the BTC futures - see below. But I wouldn't bother investing, even via the future.

Do I have enough money to invest in BitCoin?

If you've read "Smart Portfolios" then you'll know that a key issue I bring up is whether you have enough money to be diversified.

For example if you trade BTC futures then you'll need to own at least one entire coin, because thats what the CBOE future is based on (the CBOT is five coins). If you have $13K in BTC (using the current price), and that's 1.3% of your portfolio, then your portfolio must be a million bucks.

If you're brave enough to trade BTC spot then you can in theory buy less than one coin. But at a $50 transaction cost it won't be economic to trade small amounts of BTC. Using table 40 in my book it turns out that the minimum economic investment in spot BTC is currently $15,000; i.e. just above one coin at current prices.

I know there are some dollar millionaires reading this blog, but if you aren't in that category (yet) you should only invest in BTC if you can afford to buy one coin (directly or via futures); at least until the transaction fee comes down sharply.

Should you trade crypto currencies?

Does it make sense to trade crypto directionally?

Let me say:

- Volatility doesn't make something more or less attractive to trade.

- There is rarely statistically significant evidence that instrument X trends better than instrument Y; and the relatively short data history for BTC means that evidence certainly won't exist

This means that if there is a compelling reason to add BTC futures it's the same as for the investment case; they provide diversification. But there are a number of problems with trading BTC futures:

- Even at the CBOE the $ volatility per contract is relatively high (currently around $13K per year compared to about half that for the emini S&P 500) making them unsuitable except for large portfolios

- The $ margin per contract is relatively high (even once you've accounted for the volatility - this is also a problem with the VIX/V2X futures because of their skew properties)

- The volume is currently too low and falls below the minimum threshold that I use before even considering adding a contract (although it shows signs of picking up and to be fair these are very new contracts)

- The bid-ask spread makes them a relatively expensive contract - this isn't a dealbreaker but means I'd need to trade them more slowly (see chapter 12 of "Systematic Trading")

- My broker doesn't let me short the futures: this is probably the most serious issue

Would I change my mind in the future? I might, if enough of these points become less problematic. But not right now.

Can you do <x> arbitrage with crypto currency?

On the face of it BitCoin is a arbitrageurs dream. The futures price isn't in line with the spot (although the gap has closed, and there should always be a slight difference reflecting the cost of funding the cash and carry trade; though there isn't really anything like a BitCoin repo market). The futures curve is the wrong shape for similar reasons (currently the CBOE strip looks like this:

Jan 18 13,530

Feb 18 13,760

Mar 18 13,520

... which makes no sense). The cash price varies wildly across exchanges (so what is "spot" anyway?)

However I'd really be nervous about trying to exploit any of this 'free money'. Because the futures are cash settled the opportunities to take a free money spot / futures bet or curve bet aren't really there (plus the Feb, March prices are probably stale given the lack of liquidity so the curve trade may not really exist). Across exchanges its even more difficult due to all the operational problems we've already discussed (verification delays, high transaction costs, the risk of theft or trades just being cancelled on an unregulated exchange).

Conclusion

No, I'm not going to buy any BTC. If after reading this you still insist on doing so please only put a fraction of your wealth into it - and make sure you're already a dollar millionaire. And please don't ask me to discuss this subject ever again (this is doubly the case if BTC goes to $1 million - I really won't want to talk about it then).